For most lawyers, the first 10 years of a developing a legal practice defines the next 20. While developing marketable skills and practice area knowledge, lawyers are also managing their income needs and personal commitments. All of these factors influence the future of a lawyer's practice. When these factors conflict with one another, they can create stress and unintended outcomes. Also having a significant impact on a lawyer’s career is his or her ability and willingness to take risks.

From a firm's perspective, the roles and goals for a lawyer typically change based on mixes of client work, economic factors, and partner preferences. While small to mid-sized firms present fewer opportunities for lawyers to diversify the development of legal skills and practice areas, they can offer lawyers accelerated career development. A firm’s limitations on capital and the investment horizon (how long it takes to generate a return) can also impact the development of new opportunities.

Balancing an individual lawyer's personal priorities is difficult enough; successfully prioritizing both firm and personal priorities can seem impossible. Without a thoughtful process that seeks to align the development of a lawyer's career with the firm's goals and needs, the long-term success or failure of a lawyer is hit or miss.....

There is a reason that most associates do not make it to the equity partner level.

A solid practice planning process will help guide the right people to the right roles in their firm. It will also ensure that individual lawyers strategically consider their career choices while there is still time to make changes.

Who should the practice planning process include?

We recommend offering the process to anyone who wants to participate. Some firms require mandatory participation, but we recommend making the process optional after two or three years. Lawyers who derive value from an organized planning process will willingly participate. Lawyers who don’t engage in the process after two or three years should opt out.

Since everyone is different, some may prefer informal communication, a different mentoring process, or a method requiring less of a commitment to further development. While a process-oriented approach is better for most, it is not the only way to progress.

Opting Out

It is not uncommon to find lawyers who can perform at an acceptable level for their role, generate profit for the firm, but have outside priorities that limit the commitment they can or will make to career pursuits. A planning process that is not aligned with the participant’s goals is pointless. Just as relevant, is the firm’s communication of the potential consequences to a lawyer settling into a limited role.

Another example of an opt-out is more of a “suspension of the process”, which can occur when life situations interfere with career pursuits. In these instances, the process can resume later.

Finally, a higher rate of return on valuable partner and senior lawyer time is possible when invested in helping motivated and talented lawyers.

When should the process start?

The practice planning process should start in the first year a lawyer is hired. A well-structured process will help ensure that all lawyers receive senior-level attention, feedback, and direction. It can also help reduce the possibility of overlooking talented lawyers. The process also helps identify those attorneys who can progress more quickly and those who may not fit.

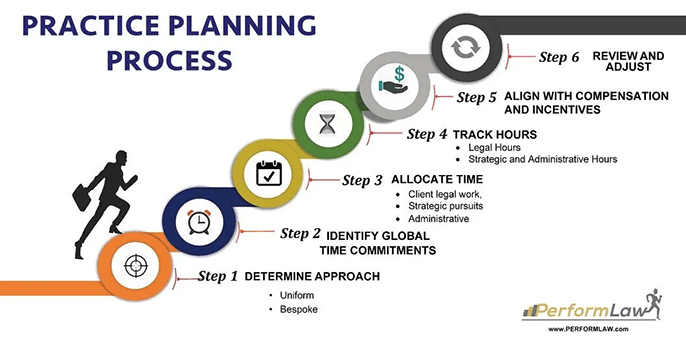

The graphic below outlines the basic steps included in a solid practice planning process.

Getting Started

The first step in the practice planning process is for the firm management to decide whether lawyers should follow a uniform or bespoke practice planning approach (See “Better Associate Performance Using a Structured Practice Planning Process”. For example, a firm may decide to use uniform practice plans that include the same elements for all first and second-year lawyers and then choose an individual planning approach beginning in year three. Once the basic approach is determined, the process of planning time commitments can begin. For the purposes of this explanation, time commitments are expressed in the form of hours.

Planning Billable (client hours) and Non-Billable Hours (strategic hours)

Plan design can include a required number of client hours, a recommended number strategic hours, and a minimally necessary number of administrative hours for each lawyer. Alternatively, a practice plan may allocate strategic hours first and legal and administrative hours second. Allocating strategic hours first is necessary when a bespoke process is used, which results in a different plan for each lawyer. After determining global time commitments, a firm can begin allocating time to specific pursuits.

Hours and time committed are synonymous. Firms that bill on a basis other than hourly may choose a more global approach to express time commitments.

The process for allocating time includes lawyers and senior leadership literally planning individual activities among the referenced categories (client, strategic and administrative) and accompanying cost budgets where applicable. In our experience, an efficient process will include a combination of surveying, form completion, published guidelines, and in person or web meetings.

Client legal hours include time spent practicing law. Strategic hours include time spent on longer-term value increases, which typically include skill development, training contributions, recruiting, marketing, new practice area development, and even Pro Bono. Administrative hours include time spent on timesheets, billing, and other nonbillable time incidental to employment.

Some activities are easier to plan than others. For example, marketing activities may include blogging, conference attendance, and client entertainment, which are easy to identify. Planning is more difficult for other factors. Trial experience, for example, may prove more difficult to obtain.

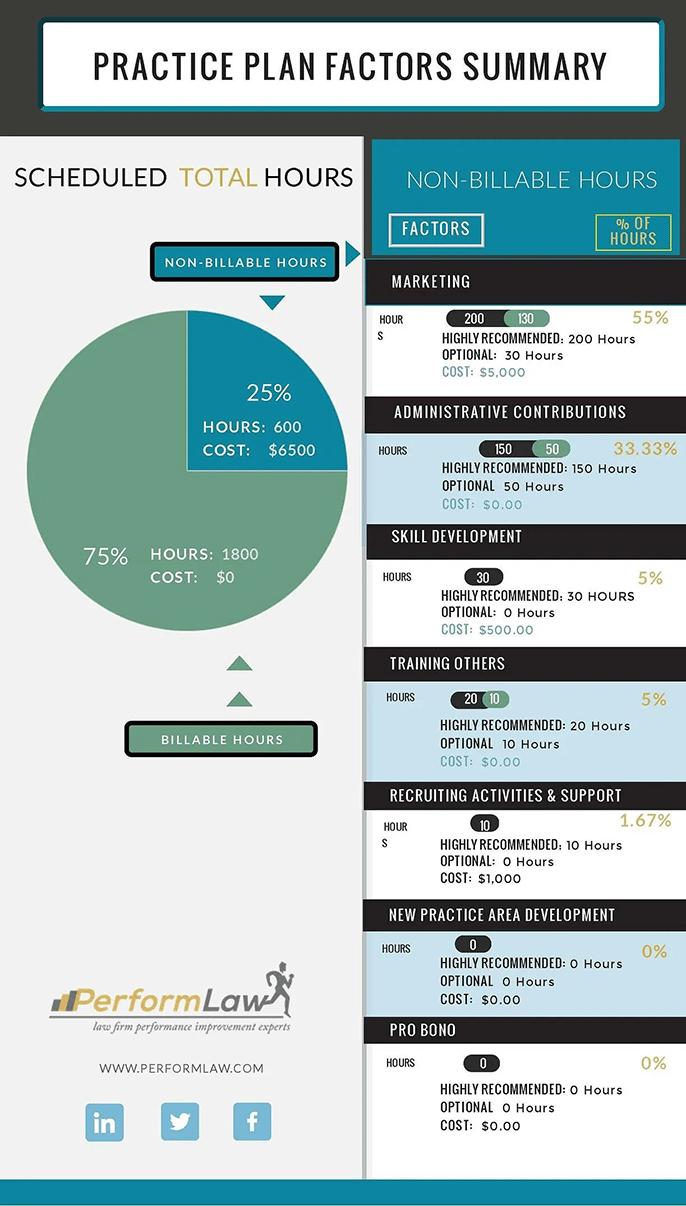

See the graphic below for an example of how an attorney's billable and non-billable hours are broken down.

Detailed activity plans make it easier to understand the time commitment a plan will require over the course of the planning interval, which is typically a year. To ensure the practicality of the plans, the initial plan development process typically concludes with a review of the individual plans, group plans, and ultimately, all of them together.

Tracking Strategic and Administrative Hours

While legal hours are usually tracked for billing purposes, it is important to also enforce the tracking of non-legal hours, preferably on a weekly basis. Tracking time for all practice plan elements can ensure that plan estimates are reasonable and can also indicate a need for adjustments to plan estimates, which typically occur quarterly. Finally, we recommend that senior lawyers periodically review plan results with those included in the planning process.

Aligning Compensation and Incentives

An important step includes aligning compensation and incentives for economic contributions and qualitative value increases in lawyer skill sets. For example, we recommend regarding economic contributions, which are mostly tied to client hours, with current year bonuses and recognizing qualitative value increases through salary adjustments, which are often the result of time spent on strategic activities. Clearly communicating the incentives and value of the contributing factors will emphasize the need for thoughtfully planning client and strategic hours.

Philosophy and the Why

In our experience, the practice planning process does not improve the performance of those who are ill-suited to their role or the firm’s practice. In other words, the process will not turn a C lawyer into an A lawyer. What we have experienced, however, is that a properly executed practice planning process retains top performers, promotes stability among good performers, and identifies those better suited for other roles or practices.

For these reasons, we encourage that firm management to establish and communicate the value of practice planning as a means of developing talented and motivated lawyers.

While the practice planning process cannot not turn a C lawyer into an A lawyer, it can retain top performers and identify those better suited for other roles or practices.

|

.webp?width=124&height=108&name=PerformLaw_Logo_Experts3%20(1).webp)